Journalism is an overlooked frontier for impact investors. It shouldn't be.

A case for financing the survival of a trustworthy media ecosystem with new ownership and capital strategies.

Caroline Ross is someone who has played a big role in strengthening local journalism across the country. She recently joined Worthmore as our first Expert-in-Residence, and together we’re building a new civic media lab. The lab is grounded in a simple idea: the future of media depends on new forms of investment to survive. Working with Caroline has sharpened something I’ve been thinking about: whether impact investors can play a bigger role in financing trustworthy news in light of attacks on the free press, and whether we need capital tools that go beyond philanthropic rescue or nostalgic preservation. This lab will be a new home for investment strategies and ownership models to support journalism as civic infrastructure.

My partner and I have outgrown our 1-BR apartment, but one reason we stay is our food co-op. New Yorkers love to poke fun at this particular co-op, though it has fierce defenders. Do I save money on groceries? Not always. Is it convenient? Absolutely not; I work a three-hour shift every six weeks. Even so, chatting with my neighbors while working the checkout counter always makes my time and effort feel worthwhile. The sense of ownership is real—hearing a shopper on the loudspeaker ask, “do we have pickles downstairs?”—and being part of this collective gives me a small sense of place that often eludes transplant New Yorkers.

Through a pure financial lens, membership makes little sense. We invest our time, money, and energy into lots of inconvenient things, not because they are rational, but because they matter to us. Over 538,000 fans of the Green Bay Packers own a piece of the team, despite no dividends, stock appreciation, or ticket perks. Retail investors have poured millions into meme stocks to stick it to Wall Street or participate in a cultural moment, often with high certainty that they will lose money.

Beyond memes and sports teams, there is latent demand for more civic infrastructure; spaces and institutions that foster connection beyond our churches, volunteer groups, and rec leagues. We’re living through a dramatic decline in civic participation (see Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone or Derek Thompson’s The Anti-Social Century) but moments like NYC’s recent mayoral upset and Mamdani’s grassroots campaign remind us that people will still show up when there’s something worth showing up for.

In A Paradise Built in Hell, Rebecca Solnit writes about “how much we want lives of meaningful engagement, of membership in civil society,” despite a culture designed via our technologies to pull us away from becoming our full selves. Local newspapers were once a cornerstone of our civic infrastructure, offering a shared source of trustworthy information and connection, but these institutions are quickly disappearing. To rebuild that sense of connection, we need a diverse ecosystem of news that helps us understand the world and each other.

This essay explores why the news is in crisis, how its business model is evolving, and what kinds of capital innovation we need from impact investors (and plan to build) to help it thrive again.

I. What happened to the news?

The business of journalism is in freefall. Since 2005, a quarter of local news outlets have shuttered, and around half of America’s daily newspapers are now owned by private equity, hedge funds, or other investment groups. The disastrous impacts of distant financial ownership are hard to overstate.

Many remaining publications have been designated “ghost papers,” an unsettling nickname for unstaffed papers that have been shelled out. From 2000 to 2020, newspapers lost 81% of their revenue. But that revenue didn’t just disappear, it’s been captured by social media platforms offering a more attractive home to advertisers. Rebuild Local News has documented the depth of this crisis in local news, where the consequences for communities are dire: lower voter turnout, less civic engagement, and more polarization.

These trends have been apparent for decades, but the lack of urgency about them may be proportional to where most people live. In densely populated places, the loss of a paper doesn’t always register. There’s always something else to read, at least for now. We don’t feel the scale of this crisis because information is so abundant. I can open my screen at any moment and see a livestreamed tennis match or illegal ICE raids. It’s hard to imagine that anything goes unreported anymore.

Meanwhile, the stakes are rising. Media companies today face two powerful headwinds: a hostile political climate and the rise of AI. The IRS, FCC, and other government agencies are increasingly being used to investigate, audit, or intimidate newsrooms and watchdog organizations, especially those critical of powerful political figures. Nonprofit journalism has become a prime target for legal threats, politically motivated audits, and ambiguous regulatory pressure. As Jesse Eisinger, Senior Editor of ProPublica, put it: “nonprofit journalism is vulnerable, and we will be tested.”

Equally distressing is the fact that AI is fundamentally reshaping how news gets distributed, monetized, and even written. Most media outlets aren’t demonstrating the capacity to keep up. From hallucinated articles (fabricated by AI platforms or published by newspapers themselves) to SEO-driven content farms flooding the internet with AI slop, the danger isn’t just misinformation. It’s the slow melt of collective human judgment to ascertain truth, what some call the “liar’s dividend.”

Legacy media, startups, and independent creators alike all lack the resources to reimagine their business models in the age of AI, widening their competitive disadvantage to the social platforms. I doubt the answer is simply more AI-generated content, yet the first full AI-generated newspaper was circulated in Italy this March. More is certainly coming.

II. The elephant in the room

It’s reasonable to ask why impact investors should put capital into journalism when the business model appears to be in crisis.

But the picture is more complicated; not every newsroom has shuttered for the same reasons. It’s true that publications still need to delight people and create in-demand products. Yet countless media outlets with dedicated readers can’t secure the capital required—capital that any small business might rely on—to hire revenue-generating staff, test new strategies, or weather unexpected shocks. When publications can’t find this capital, we lose more than a business. We lose a public good.

There is also a case for returns. As Jack Shafer writes in Politico, “In 2021, the U.S. newspaper industry generated $20.9 billion in revenue with profit margins just below 4 percent. That’s down from its wonder years, but it’s hardly a knockout.” It doesn’t come without challenges, but the news can be investible with the right combination of patient capital and inventive business models.

What do these models look like? Subsidizing media with non-media products is one way to do it. The New York Times is arguably now a gaming company that also writes news. By some estimates, nearly three-quarters of Bloomberg’s revenue comes from Bloomberg Terminal, its finance software.

In Marfa, Texas, The Big Bend Sentinel sustains itself through a mix of revenue from the paper and The Sentinel, its cafe and event space. Co-owner Max Kabat has asked: “Why is it that local journalism has always depended on the same two revenue streams of ads and subscribers? If one of a newspaper’s jobs is to build community by capturing the history of a place and its people, why should we be confined to only print and digital news and information products?”

Multi-local outlets, newsrooms that cover different communities with a common parent, are also taking a new approach to an old model, as ProPublica’s founder Dick Tofel explores on Substack. The Texas Tribune, for instance, is launching a network of local newsrooms designed to “inform, empower, and engage Texans at the community level.”

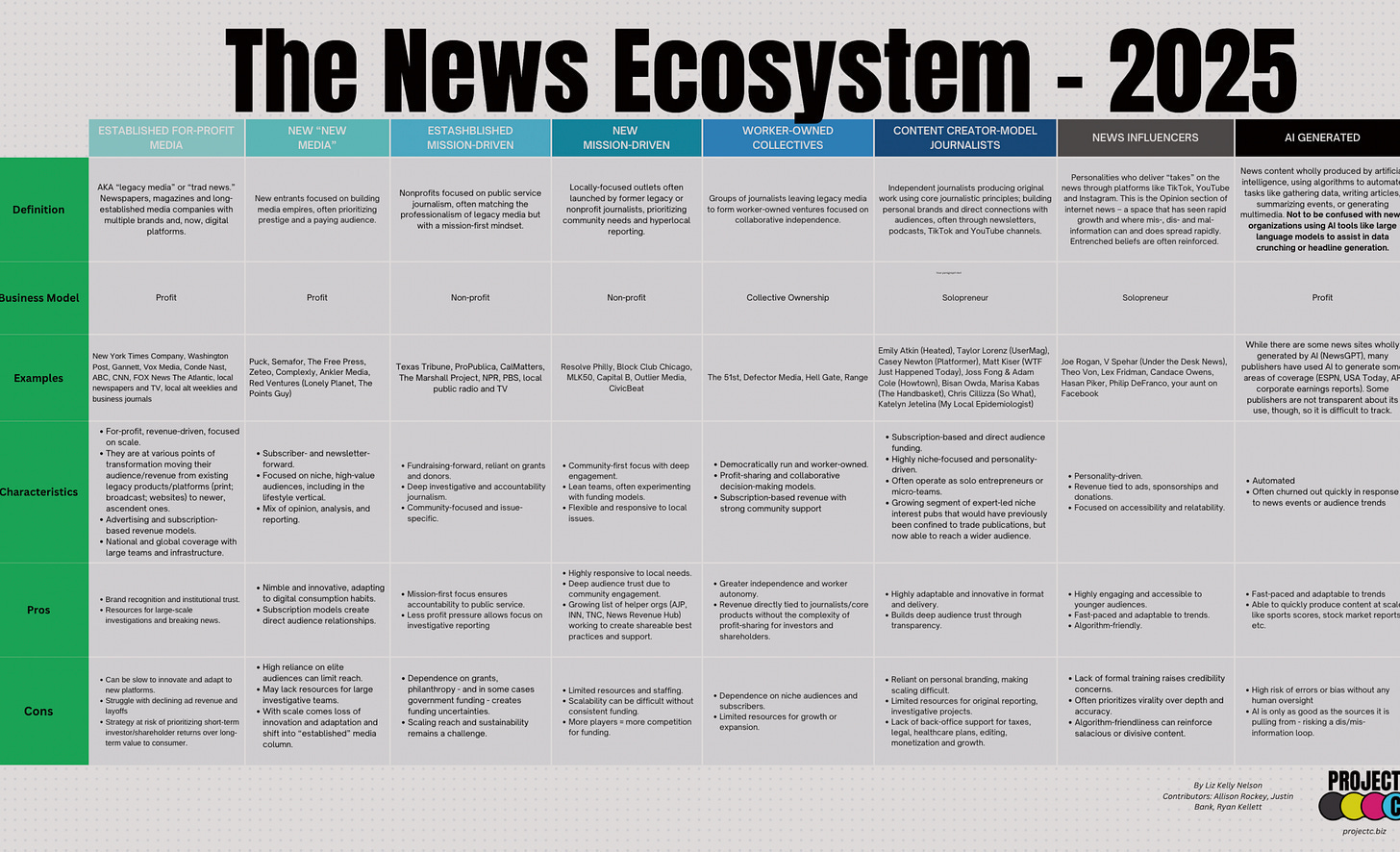

Widening the aperture around what counts as journalism can also uncover high-potential ventures. College professor Heather Cox Richardson’s Substack newsletter, Letters from an American, now has more than 2.6 million subscribers, and by some estimates is generating $1 million per month. Imagine the opportunity to invest in this ecosystem of next-generation independent creators increasingly drawing readers away from legacy platforms with distinctive content. Today, it’s all about the personal brand, even when multiple people work behind the scenes, much like a traditional newsroom. (Project C is a great resource for exploring creator-model journalism and the evolving news ecosystem.)

III. How impact investors can help rebuild the news

Taken together, these examples show that there is no shortage of media entrepreneurs asking the hard questions and fighting for the future of news. The question now is not what models are possible, but how do we invest in them.

Philanthropy has provided a valuable source of capital for new media, and funder collaboratives like Press Forward and incubators like Glen Nelson Center have led the charge. But philanthropy alone can’t address the deeper structural financing challenges of this sector. Grants can buy time to experiment and grow, but they rarely build the balance sheets needed to withstand revenue swings, political pressure, or platform shifts. As Adam Thomas writes in Nieman Lab, “the financing models rarely fit the unique challenges of media organizations and products, where the value is long-term and intangible.” That gap is where impact investors can step in.

While a new wave of impact investors are developing innovative tools built around equity and sustainability, this mindset is rarely applied to media. Perhaps it’s a sector perceived as risky, slow-growing, or in decline. But catalytic capital, flexible financing strategies across debt and equity, and blended vehicles could finally bring the resources and experimentation that journalism needs.

Here’s the opportunity for the lab we’re building. It’s not only to protect journalism, but to create financial tools that match the emerging ownership and business models taking root across the country.

We’re especially interested in civic media—local news, niche digital outlets, independent creators, worker-owned media cooperatives, and media infrastructure oriented toward public service. The investment tools might look like equity or revenue-based financing for infrastructure developed by creators, a blended fund that enables community ownership of a local paper, or bridge loans to help enterprises navigate AI disruption. Rebuild Local News has a great paper outlining more of these strategies.

Beyond financing, there are deeper questions about who should own and govern the news. We know that when corporations and wealthy individuals purchase outlets, journalistic integrity often suffers. But what’s the alternative? We’re inspired by worker-owned outlets gaining momentum, like Defector—a spinout of former Deadspin employees that is already profitable—and at least six more entities that launched in 2024. Reflecting on the corporate ownership they deliberately left behind, Defector’s editor-in-chief wrote, “Who ultimately wins when publications start acting less like purpose-driven institutions and more like profit drivers, primarily tasked with achieving exponential scale at any cost?”

What if media outlets operated more like co-ops or community-owned newsrooms? Substack has proven that people are willing to pay $5 or $10 not only for trusted content, but for the chance to connect with others through comments and live dialogue with the writer. Now imagine owning a stake in your local paper, not to steer what gets published, but to help elect a board that ensures the newsroom stays accountable to its community.

Still, we have more questions than answers. Which media ventures (local, creator-led, community-owned, or platform-based) are ready for investment? What capital tools (loans, grants, equity, blended finance) best match these models? What revenue strategies can help civic media grow and thrive? What infrastructure can support these ventures in uncertain times?

If we want a future where someone still shows up at the school board meeting or files the FOIA request, we can’t just hope news survives; we have to choose to fund it. Over the next few months, our team will be exploring how to do this with Caroline Ross, who has helped conserve 64 newspapers across Colorado, Maine, and Georgia through a mission-driven M&A strategy and pioneered shared operating infrastructure for the future of media. I’m honored to be working alongside Caroline to pilot this work, and if you’re interested in getting involved as a funder or partner, we’d love to connect.

This is a fantastic and vital piece, Caitlin. You've perfectly articulated a point that often gets lost: the journalism crisis isn't just about the business model, it's about the capital model.

Framing the solution around the need for new impact investing tools is the critical next step for this conversation. Our thinking is very aligned on this. I explore similar case studies and strategic frameworks on my Substack, "Backstory & Strategy," and think you might find some of the pieces relevant to the work of your new lab.

I'd love to connect and follow your work more closely.